Afonin Pavel Ivanovich

(1920–2011)

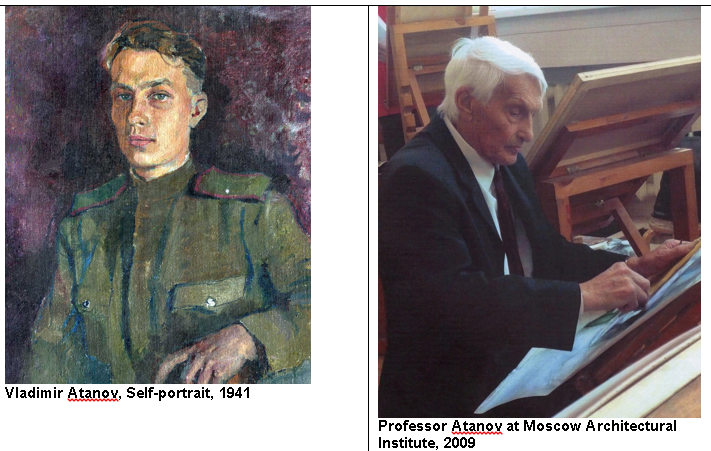

He was the thirteenth child in a peasant family from central Russia — an unlucky number in this part of the world, where people are generally known to be superstitious. His mother had little hope of seeing her youngest offspring grow to adulthood since several of her children died in infancy. However, Pavel Afonin would go on to live through and take active part in some of the most horrific and extraordinary events in Russian history - collectivisation, purges, war – to witness Perestroika and the dawn of Putin’s Russia. Pavel Afonin would have turned 100 this June, although his real date of birth even his own mother couldn’t remember. What kept him going was stamina, self-discipline, art and a sense of humour.

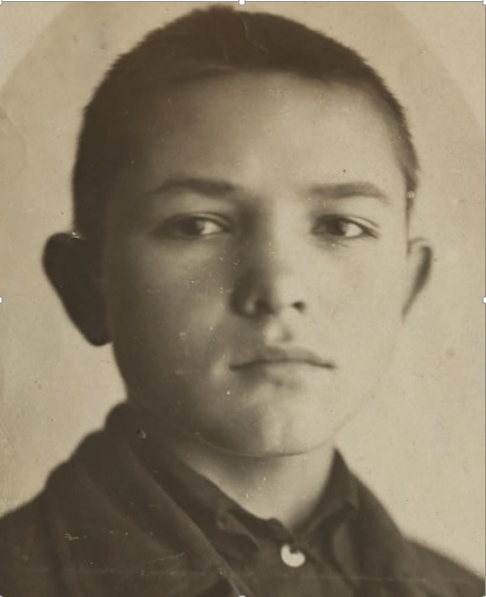

Pavel Ivanovich Afonin was born in 1920 in the small village of Noviy Mochim in the Pensa region. He was the youngest (13th) child in the family. His father, Ivan Ignatievich Afonin, had a farm, where his children helped out to the best of their ability. From the age of five, Pavel would sit on horseback as his elder brothers and sisters ploughed the fields. It was then when he discovered his passion for drawing. His relatives recalled that he used to draw with anything he could find: chalk, a piece of coal. And he had a good eye for detail.

Then the collectivisation began. Pavel was still a young boy, but he remembered vividly when armed representatives of the new Soviet state came to appropriate all the family’s cattle and equipment, and how his father was arrested on charges of espionage – an absurd accusation, seeing that he had never left the village in his life. While he was being escorted to the regional centre, he managed to escape and get to Tula, where his elder brother lived.

Pavel’s elder brother David was also arrested and exiled to Siberia as the son of a “kulak,” which was the term used for well-off peasants, who worked on their own land. David and his wife died in Siberia from typhus.

Soon the rest of the family reunited in Tula and began a new life. At first, they starved, and Pavel had to beg to provide for the family until his father found work. Pavel still vividly remembered in his late years how he was once badly bitten by a guard dog at one of the private steads he entered asking for food for his unwell mother, as his father was still in hiding. It was difficult to find any work and he had to accept a position as a groom and carpenter. Soon after, he was lucky to be employed as a guard at a bakery, which allowed him to feed his family. Pavel was ten years old and worked as a herdsman to make ends meet.

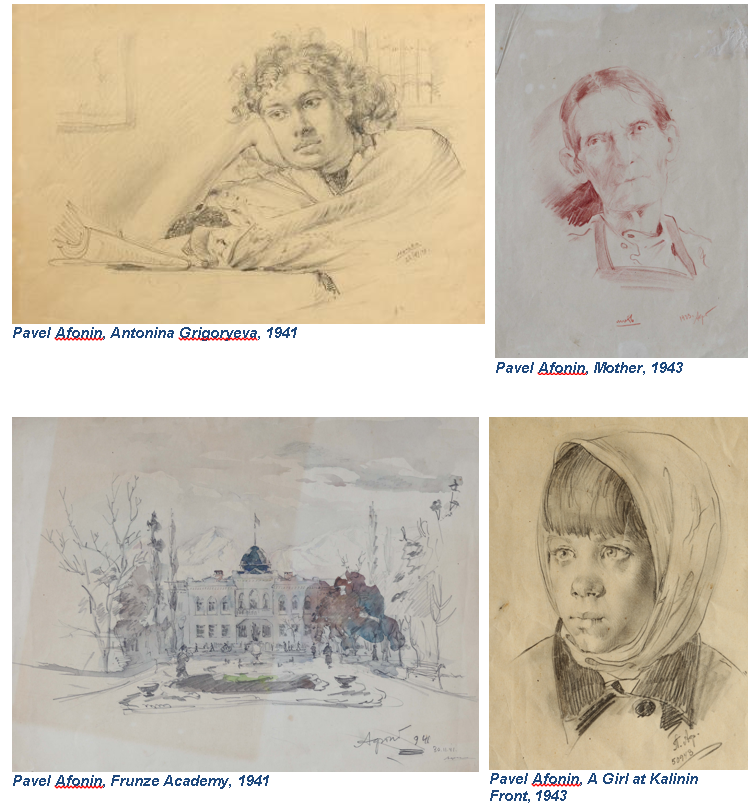

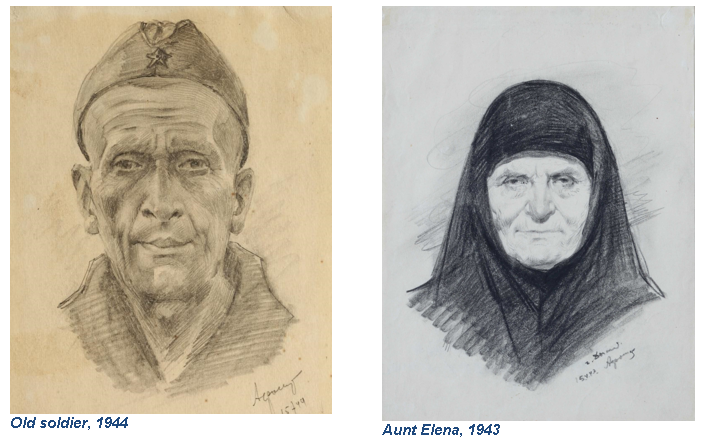

He began drawing with a pencil when he was five years old. His formal education in drawing and painting began in Donskoi, where he attended art classes under the supervision of the artist Vasiliyev and later Nikolai Samokish, an acclaimed painter of battle scenes, who recommended that Pavel try to enter the Academy of Arts. His elder brother Maxim encouraged Pavel to go to Moscow. However, when Pavel arrived in the capital, the application process for the Academy was already closed and he was advised to go the Moscow Architectural Institute instead where the exams were still taking place. Pavel passed the drawing exams with the highest grade and entered the school of architecture. He was 16 years old and the youngest in the class. It was there were he met his life-long friend Vladimir Atanov, with whom they shared experiences of both art and war. Vladimir Atanov later became a prominent watercolour painter and lead the department of painting at their alma mater institute. At one of the dance balls at the institute he became acquainted with Antonina Grigoryeva who would later become his wife.

Pavel had just finished his third year at university, when war broke out in the Soviet Union in 1941. He recalled that day of Sunday, 22 June in minor details. His brother Maxim came to Moscow to greet Pavel with accomplishing his studies with the highest grades. Pavel lived in a student dormitory near “Sokol”. “We had a lovely cup of tea with sugar cubes and both went to a local barber for a haircut. I was there when we heard Vyacheslav Molotov’s announcement that the Nazis had crossed the border of the Soviet Union and the war began. Silence fell in the barber shop – no one knew what to think or expect”, described Pavel that first day of the war in his late nineties.

The best students were given the task of saving the most important architectural buildings and monuments in Moscow from Nazi air attacks. Pavel Afonin took part in camouflaging the building of the Bolshoi Theatre, which was a complicated job. Soon after, Pavel was selected to join The Military Engineering Academy named after Kuibyshev, based in the town of Frunze in Kirgizia (now Bishkek), where officers of the engineering forces received their training.

In 1942, after finishing the course, Pavel was sent to the Kalinin Front but prior to this was granted leave to visit home. During this short trip to Moscow he proposed to his future wife Antonina who was an art student in Moscow. Pavel recalled how he came to visit Antonina’s family in central Moscow only to learn from her sister that she was about to marry a respected NKVD colonel. Heartbroken, he decided to leave but chose to walk the length of the long hallway of the communal flat on his hands. (The flat formerly belonged to Antonina’s family, but after the Revolution was shared with eight more families; eight to ten people to a room).

This antic attracted the attention of the bride-to-be and, most importantly, of her father Gavriil Parphiryevich, who was fond of Pavel. He called the young man aside, and told him not to give up and come back tomorrow. Pavel brought a present, or a kind of dowry, of 10 kilograms of butter which was a very rare find those days. This helped to melt Antonina’s mother’s heart and they agreed to the marriage. Antonina herself had little say over it. She remembered thinking him a pleasant boy who made her laugh, but she hardly knew him at all. As Pavel was going to the front, she did not want to upset him; besides, she preferred him to the other prospective husband who came across as ‘boring and stuck up’. This is how their union was born in the middle of war and continued for over fifty years until Antonina Afonina passed away.

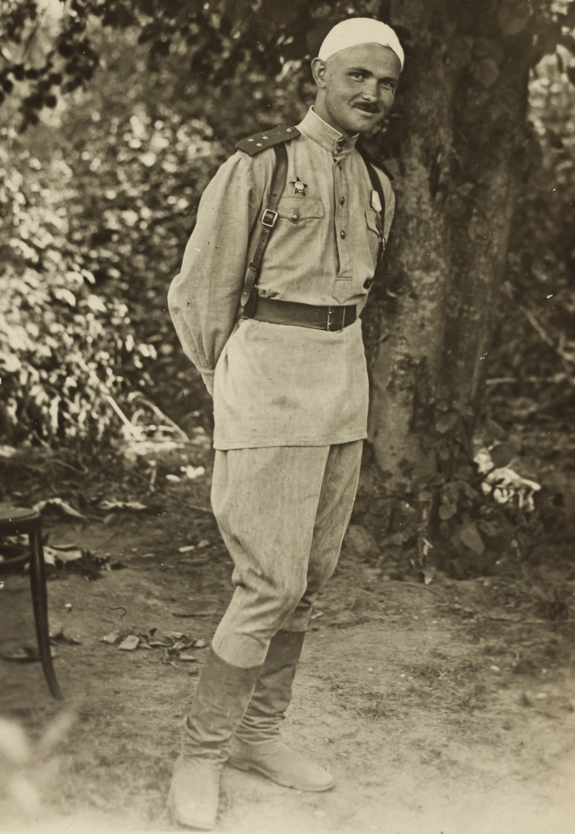

Sergeant Pavel Afonin thus described his arrival to the Kalinin front: “From Frunze via Moscow we were sent to the Kalinin Front. When I arrived, I felt a distinctive stink of death and saw many white patches all around…it took me some minutes to realise that they were the bare feet of corpses…”

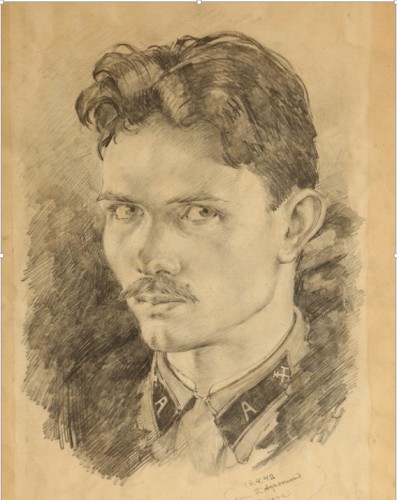

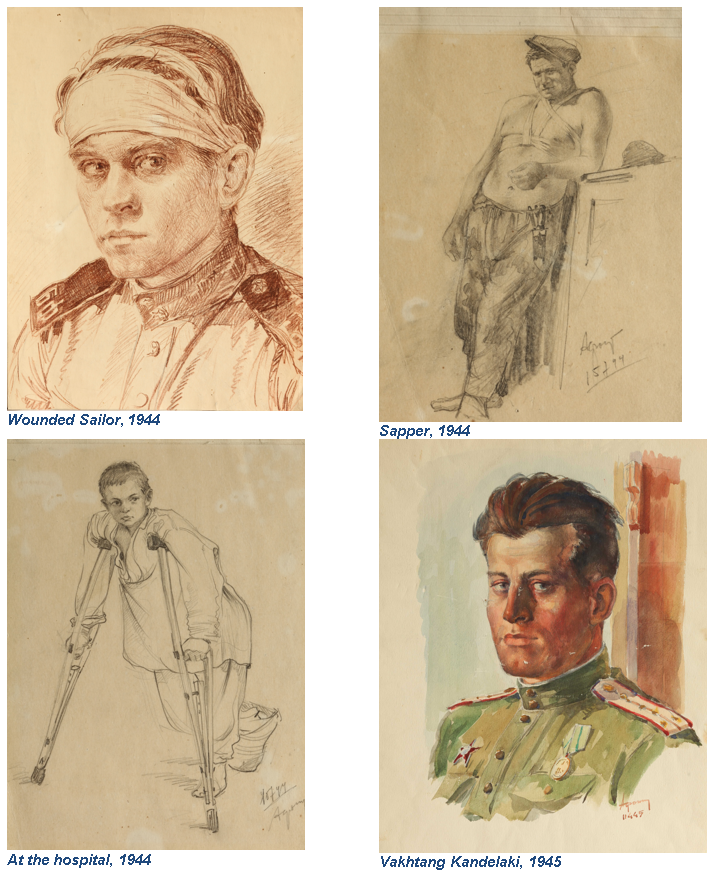

But there was no time to dwell on the vagaries of life and death. In a month, he became commander of an engineer-sapper unit as part of the 17th Brigade of the 5th Shock Army, which he led until the end of the war. He never stopped drawing. In the rare moments of rest between battles, he created over two hundred portraits of his brothers-in-arms and sketches of life at the front.

Pavel’s unit took part in liberating Leningrad, Vyborg, Poland and Estonia, as well as the Berlin operation. In 1945, as commander of an engineer reconnaissance team, Pavel was ordered to build a crossing over the Oder near Kienitz. This was in the midst of one of the hardest operations of the Second World War, when both sides suffered tremendous losses. Pavel recalls: “Several battalions were allocated for the construction of the crossing. We cut down pine trees 12–14 meters long to build dams as the ice on the river was thin and couldn’t hold tanks. The area was permanently bombed and strafed by Nazi scout planes and many of my comrades-in-arms never reached the other side of the river.”

During the Vyborg offensive in 1944 Pavel suffered a serious concussion. A shell fragment nearly pierced his brain, but Pavel miraculously survived. He spent about a month in a hospital near Vyborg where he created a series of drawings.

“This was part of the operations of the Leningrad Front, we participated in the liberation of Gatchina, where at the last minute we managed to deactivate mines set in the Gatchina Palace, then fought to lift the Siege of Leningrad and stormed Vyborg. There, I was twice seriously wounded in the head by shrapnel. I survived thanks to a sudden cease fire ordered by Mannerheim. My comrade, the regimental doctor Vakhtang Kandalaki, saved my life by swiftly operating on me at that time. On the same day, 5-10 minutes prior to the second injury, I accidentally ran into my close friend Volodya Atanov. I remember how through the shell noise I suddenly heard his cry “Pasha!”’

Volodya was also known for his good sense of humour, which he employed in the most unexpected circumstances. He recalled seeing Pavel walking towards him with blood streaming from a head wound over his uniform and medals, and thinking how he wished to capture the scene in watercolours as it was so colourful. But when he shared his thoughts with his wounded friend, Pavel failed to find it amusing. They used to exchange jokes about that meeting after the war, whilst raising glasses to Carl Mannerheim for saving Pavel’s life.

Pavel was among the first to reach Berlin as part of the 5th Shock Army, commanded by Marshal Zhukov. He received multiple medals and several Orders for his services during the war: the Order of the Red Star, two Orders of the Great Patriotic War (1st and 2nd Class), Order for Services to the Motherland, and eighteen medals, including one for defending Leningrad.

Vladimir and Pavel met three times during the war – which was a very rare coincidence as they were part of different forces. Vladimir fought in the infantry, whilst Pavel was part of an engineer-sapper unit. They continued their special friendship after the war until their last days.

After the end of the war, both friends returned to Moscow to finish their education in architecture. Pavel graduated with honours from the Moscow Institute of Architecture in 1948. Two years later he was called up again for military service to rebuild Kaliningrad, which had been completely destroyed during the war. There he met Vladimir again and they worked together on rebuilding the city. In the middle of the 1950s, Pavel and his family moved to Leningrad. Pavel’s wife, Antonina Gavrilovna Afonina, became an acclaimed sculptor and painter. She created public monuments to national heroes and political leaders in Kaliningrad and Leningrad, and worked as a drawing teacher.

While working at the Komarovsky Military Engineer-Construction Institute in Leningrad, Pavel defended his doctoral thesis and headed the Department of Architecture over a period of sixteen years. He stopped teaching when he was over 80 years old. Until 2008 Pavel delivered lectures on architecture, served on the examination board and continued drawing.

Vladimir returned to Moscow after Kaliningrad and continued his professional development at the Architectural Improvements Faculty of the Moscow Architectural Institute. He worked on creating some of the historic landmarks of the Russian capital, including the Palace of Soviets of the USSR. In 1979, Atanov returned to the Moscow Architectural Institute as a professor of painting. From that moment on, watercolour painting and teaching became the main work of his life until his final days.

The two friends used to visit each other regularly throughout their lives. They loved to paint and joke, whilst recalling their shared experiences of war and peace. Professor Afonin passed away in the age of 91. Professor Atanov followed him a few days later.

This story is a small tribute to my grandfather, his family and friends and all people of his generation who advocated important human qualities of integrity, loyalty, courage, endurance, perseverance, friendship, humour and creativity. I believe that there is still lots for us to learn from them and our shared past.

Ksenia Afonina,

Russian Cambridge Society